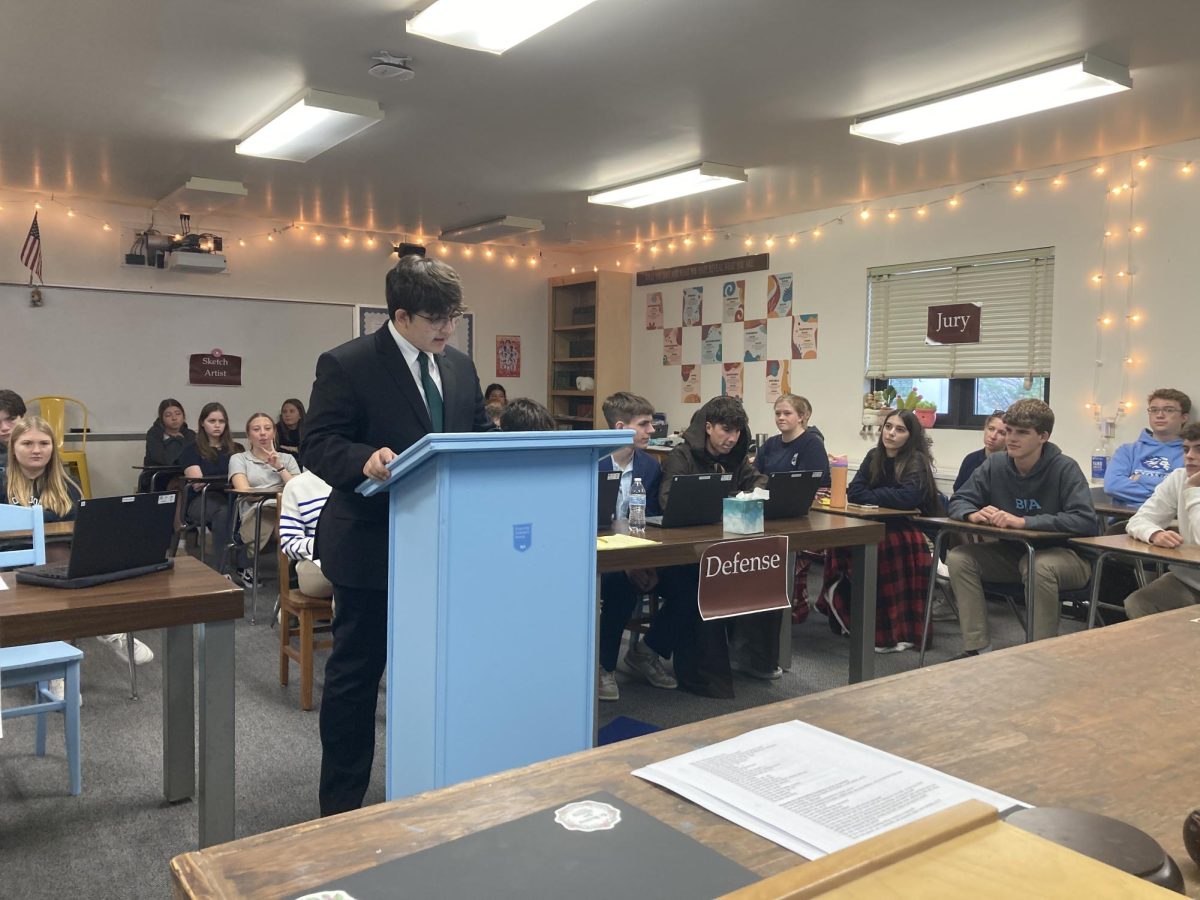

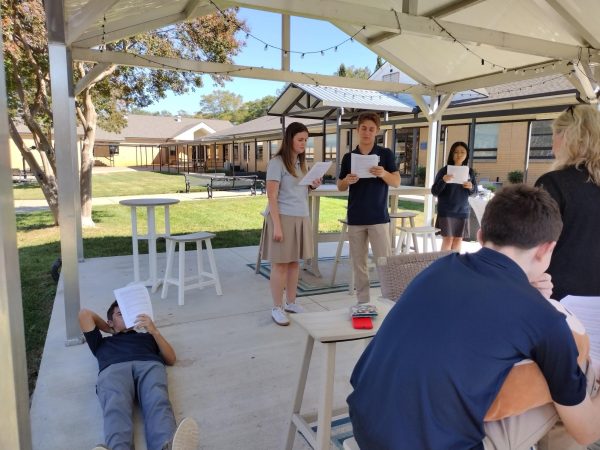

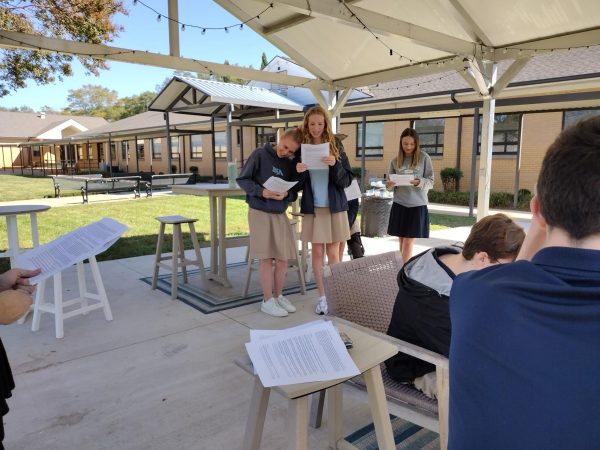

On Thursday, October 24, the junior English classes acted out a scene from The Deerslayer by James Fenimore Cooper.

The Deerslayer opens with Deerslayer’s arrival at Glimmerglass to keep a rendezvous with Chingachgook, a Mohican chieftain, whose fianceé has been kidnapped by the Iroquois. After warning Thomas Hutter, a fellow settler, and his two daughters of the hostile Indians, the colonists and Chingachgook all retreat to the Hutters’ fortified dwelling built on an island in the lake. That night Deerslayer and Hutter return to the mainland to retrieve two canoes. Hutter is captured, and Deerslayer, unable to rescue him, falls asleep in one of the canoes. When he awakes in the morning, he finds that the other canoe has drifted away. In this adapted excerpt, he now attempts to recover it.

٭٭٭

Deerslayer paddles his canoe to the shore, then lays down the paddle and picks up his rifle. As he raises his rifle, a pistol shot rings out. A bullet whizzes past his body, and he reacts by falling into the bottom of the canoe. A voice yells out, and an Indian leaps from the bushes, bounding towards the canoe. Deerslayer rises in the canoe and levels his rifle at the Indian, but he hesitates because he considers the Indian to be at a disadvantage. The Indian bounds back into the bushes, and Deerslayer approaches the land. His canoe touches the shore a few yards from the other canoe. He doesn’t have enough time to secure the second canoe without being exposed to another shot.

Deerslayer dashes for cover in the woods. As he shields himself behind a tree, he glimpses the arm of the Indian, also hiding behind a large oak tree, in the very act of reloading his rifle. It would be so easy to spring forward and finish off the Indian, but every feeling of Deerslayer revolted at such a step since his enemy was unprepared. It struck him as an unfair advantage to assail an unarmed foe.

Deerslayer drops his rifle to a carrying position and mutters under his breath, “No, no – that may be redskin warfare, but it’s not a Christian’s gift [characteristic]. Let the miscreant charge, and then we’ll take it out like men; for the canoe he shall not have. No, no, let him have time to load, and God will take care of the right!”

The Indian, not noticing that his enemy is close-by, loads his rifle and steps out of the woods. Deerslayer steps out as well.

“Thisaway, redskin; thisaway if you’re looking for me,” Deerslayer says. “I’m young in war, but not so young as to stand on an open beach to be shot down like an owl by daylight. It rests on yourself whether it’s peace or war atween us; for my gifts are white gifts, and I’m not one of them that thinks it valiant to slay human mortals, singly, in the woods.”

The Indian is startled but is also crafty. He drops the butt of his rifle to the earth and makes a gesture of courtesy.

“Two canoe,” the Indian says, holding up two fingers, “one for you – one for me.”

“No, no, Mingo, that will never do. You own neither, and neither shall you have, as long as I can prevent it. I know it’s war atween your people and mine, but that’s no reason why human mortals should slay each other, like savage creatures; go your way then, and leave me to go mine.”

“Good! My brother missionary – great talk; all about Manitou.”

“Not so, not so, warrior,” Deerslayer objects. “I’m not good enough for the Moravians and am too good for most of the other vagabonds that preach about in the woods. No, no, I’m only a hunter, as yet, though afore the peace is made, ‘tis like enough there’ll be occasion to strike a blow at some of your people. Still, I wish it to be done in fair fight and not in a quarrel about the ownership of a miserable canoe.”

“Good! My brother very young – but he very wise. Little warrior – great talker. Chief, sometimes, in council.”

“I don’t know this, nor do I say it, Indian, I look forward to a life in the woods, and I only hope it may be a peaceable one. All young men must go on the warpath, when there’s occasion, but war isn’t needfully massacre. I’ve seen enough of the last, this very night, to know that Providence frowns on it; I now invite you to go your own way, while I go mine, and hope that we may part friends.”

“Good! My brother has two scalp – gray hair under the other. Old wisdom – young tongue.” They shake hands. “All have his own, my canoe, mine; your canoe your’n. Go look: if your’n, you keep, if mine, I keep.”

“That’s just, redskin, though you must be wrong in thinking the canoe your property. However, seein’ is believin’, and we’ll go down to the shore, where you may look with your own eyes; for it’s likely you’ll object to trustin’ altogether to mine.”

“Good!” the Indian agrees.

The two of them walk towards the shore side by side. The Indian points to Deerslayer’s canoe and says, “No mine – paleface canoe. This red man’s. No want other man’s canoe – want his own.”

“You’re wrong, redskin, you’re altogether wrong. This canoe was left in old Hutter’s keeping, and is his’n according to all law, red or white, till its owner comes to claim it. Here’s the seats and the stitching of the bark to speak for themselves. No man ever know’d an Indian to turn off such work.”

“Good! My brother little ole – big wisdom. Indian no make him. White man’s work.”

“I’m glad you think so, for holding out to the contrary might have made ill blood atween us, everyone having a right to take possession of his own. I’ll just shove the canoe out of reach of dispute at once, as the quickest way of settling difficulties.”

Deerslayer puts a foot against the end of the canoe and gives it a shove. The Indian looks at Deerslayer’s canoe with a hurried and fierce glance, then smiles again.

“Good! Young head, old mind. Know how to settle quarrel. Farewell, brother. He go to house in water – muskrat house – Indian go to camp; tell chiefs no find canoe.”

Deerslayer is pleased with this, and he shakes the Indian’s hand willingly. The Indian walks away calmly towards the woods, with his rifle in the hollow of his arm. Deerslayer walks toward the canoe in the same manner, but keeps his eyes on the Indian. He turns away when he reaches the boat and prepares to depart.

Deerslayer glances up again and his quick and certain eye tells him at a glance the imminent jeopardy in which his life is placed. The Indian is crouching in the bushes, and the muzzle of his rifle is visible through a small opening in the bushes. Deerslayer’s experience as a hunter takes over. To cock and aim his rifle were the acts of a single moment and a single motion. At the same time, Deerslayer and the Indian fire at each other. Deerslayer drops his rifle and stands.

The Indian yells and leaps through the bushes, holding a tomahawk. Deerslayer never takes his eyes off the Indian but feels for his powder horn. The Indian hurls the tomahawk, but his hand is so unsteady that Deerslayer is able to catch it by the handle as it flies past him. The Indian staggers and collapses.

“I know’d it, I know’d it!” Deerslayer exclaims, “I know’d it must come to this as soon as I saw the creature’s eyes. A man aims and fires quick when his life’s in danger. I was about a hundredth second too quick for him, or it might have been bad for me! Say what you will for or ag’in ‘em, a redskin is by no means as certain with powder and ball as a white man. Even Chingachgook, great as he is in other matters, isn’t downright deadly with the rifle.”

Deerslayer goes to the Indian and stands over him, leaning on his own rifle. It was the first fellow creature against whom he had ever raised his own hand. The Indian, still conscious, probably expects Deerslayer to scalp him.

“No, no, redskin, you’ve nothing more to fear from me. I am a Christian, and scalping is not of my gifts. I can’t stay much longer, as the crack of three rifles will bring some of your devils down upon me. All enmity atween you and me’s at an end, redskin.”

“Water! Give poor Indian water!”

“Aye, water you shall have, if you drink the lake dry. They tell me, with all wounded people water is their greatest comfort and delight.”

Deerslayer carries the Indians in his arms to the lake. He helps him take a drink, and then puts his head in his lap.

“It would be sinful of me to tell you your time hadn’t come, and so I’ll not say it. Considering the sort of lives you lead, your days have been pretty well filled. The principal thing, now, is to look forward to what comes next. Neither redskin nor pale-face, on the whole, thinks much about death, but both expect to live in another world. You’ll find your happy hunting grounds, if you’ve been a just Indian. I’ve my own ideas, but you’re too old and experienced to need any explanations from one as young as I.”

“Good! Young head – old wisdom!”

“It’s some consolation to know that them we’ve harmed forgive us. Now, as for myself, I overlook your attempts ag’in my life, because I can bear no ill will to a dying man, whether heathen or Christian.”

“Good! Good – young head; young heart, too. Old heart tough; no shed tear. Hear Indian when he die, and no want to lie – what he call him?”

“Deerslayer is the name I bear now.”

“That good name for boy – poor name for warrior.” The Indian taps Deerslayer on the chest. “No Deerslayer – Hawkeye – Hawkeye – Hawkeye.”

Photos courtesy of Shannah Lin